Understanding the Hierarchy of Control: Practical applications across industries

Bridget Leathley explains what a Hierarchy of Control is, why they’re needed and how to implement them.

In the UK, the Health and Safety at Work Act (HSW) requires employers to “ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare” of people. This sets an expectation that employers can and will control the hazards that arise from their business. For instance, don’t create or use chemicals if you don’t understand how to handle them safely, don’t work on a roof if you don’t understand how to control work at height risks.

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (MHSW) list nine requirements in Schedule 1 for how to achieve this control. This list is the starting point for what has become known as a ‘hierarchy of controls’. As we will see, it’s not really a hierarchy, but it does provide a basis for the order in which you should consider controls when trying to improve your ability to “ensure health, safety and welfare”.

The first of the nine requirements in MHSW is “avoiding risks.” Perhaps because ‘avoidance’ seems a rather weak approach, most versions of the hierarchy start with the stronger and clearer recommendation to eliminate the hazard.

Once you’ve evaluated the hazards that can’t be eliminated, MHSW Schedule 1 asks you to combat the risks at source. The rest of the list is useful but shouldn’t be seen as a hierarchical or prioritised list – for example, replacing old equipment with new equipment which reduces noise and vibration could be an example of both (e) adapting to technical progress and (f) replacing the dangerous with the less dangerous.

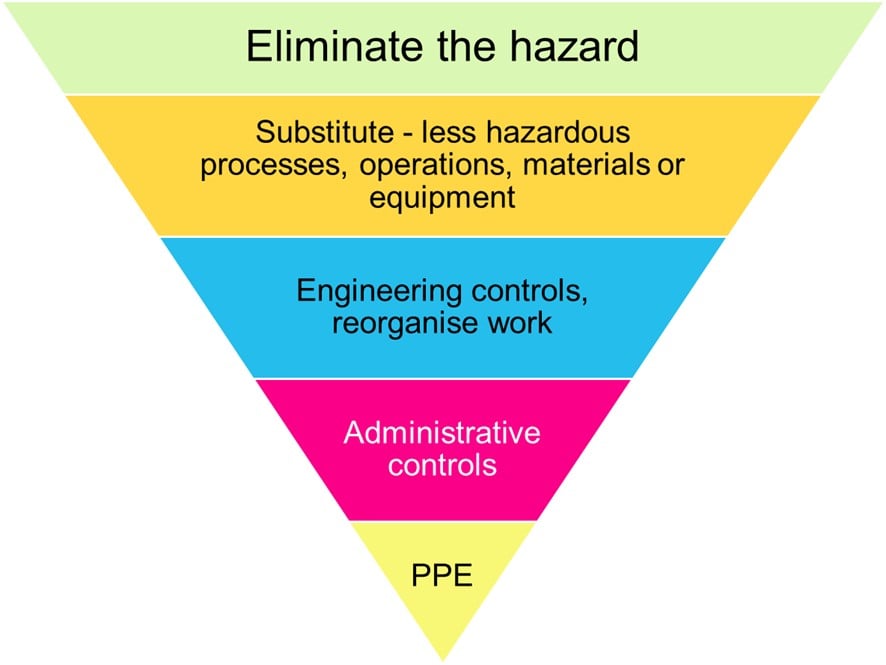

Other safety legislation provides lists of controls tailored to particular hazards. For example, for hazardous substances, work at height and noise. The Occupational health and safety management systems standard, ISO 45001 (section 8.1.2) simplifies these lists into a single, shorter hierarchy which is easier to remember, and is used on NEBOSH courses. These are often represented as distinct layers in a triangle, with eliminate at the top and PPE at the bottom as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A generic hierarch of control

Figure 1: A generic hierarch of control

What you find when you try to apply this hierarchy to risk assessments in the real world is that there are overlaps that blur the separate layers, and dependencies which mean you usually need controls from multiple layers to create an effective control system.

Every context is different, so as you read the examples below, think about how you’d apply them to your own workplace.

WAH in construction

For work at height, the ‘eliminate’ step means not working at height. In an office this is a practical strategy – don’t store documents so high that people need to use a ladder (or worse, to climb on a chair) to reach them. Store everything where it can easily be reached.

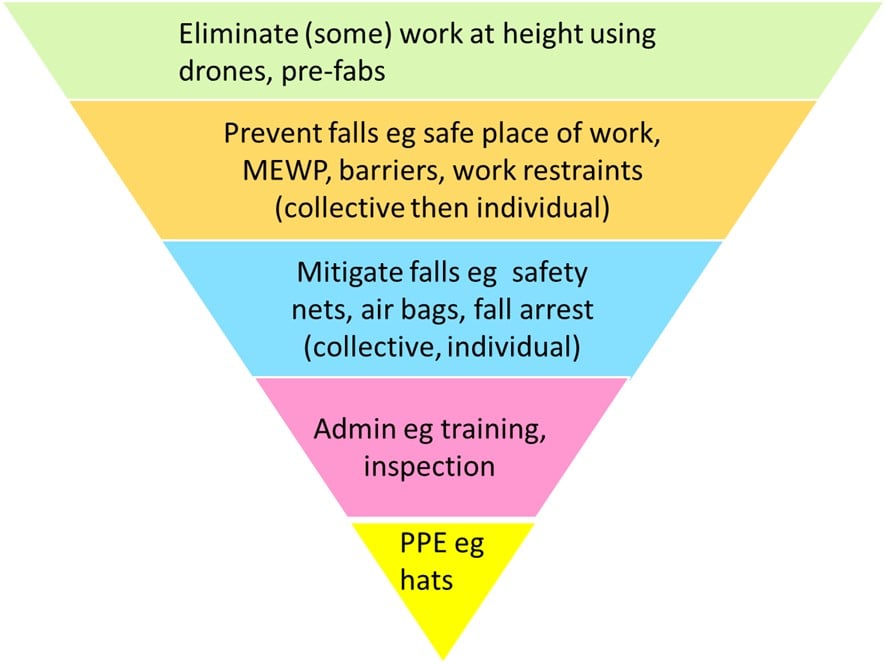

If you are building a wall for a three-storey building, at some stage someone needs to be two floors up to build the third floor. Drones with cameras might limit the number of times a supervisor needs to climb for inspections, and pre-fabricated buildings might reduce the time at height for construction, but complete elimination is unlikely.

The Work at Height Regulations move from avoiding work at height as the first step (6(2)) to preventing falls (6(4)) and then to mitigating falls (6(5)).

Within these last two categories, collective measures are noted as being more effective than individual ones. It would be wrong to use the hierarchy to suggest that an individual method to prevent a fall, such as a work restraint, excluded the need for a collective measure to mitigate a fall, such as a safety net. In the absence of more effective practical measures, you might need the work restraint and the safety net.

Having the right work equipment is no use if nobody has checked it’s in good condition. In July 2025 Glasgow Prestwick Airport was prosecuted after an experienced worker died when a corroded guardrail failed. The maintenance programme at the time of the accident did not include checks for deterioration of the guardrail. Without this administrative control, the higher order control of preventing a fall with a collective barrier was ineffective.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is regarded as ‘the last resort’, but where a hazard hasn’t been eliminated, PPE can be an essential part of your control system. A hard hat will do little for the person falling from the scaffold, but if other measures fail to prevent the person on the scaffold dropping a tool (and administrative controls haven’t prevented someone walking underneath the work area), a hard hat could provide the final layer of control that prevents a serious head injury. And safety boots with penetration-resistant soles could prevent a foot injury to the worker who steps on the tool that fell from height earlier in the day.

Figure 2 illustrates how these controls relate to each level.

Figure 2: Controlling work at height in construction

COSHH control for cleaners

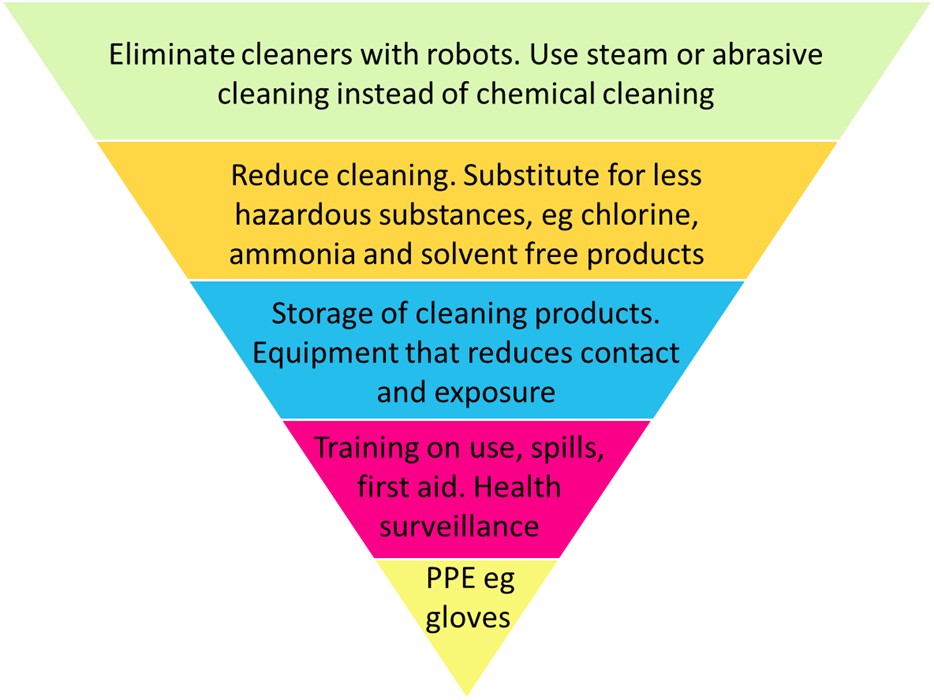

Unless we lower our hygiene standards, eliminating cleaning is not practical. Replacing human cleaners with robot cleaners would be an example of ‘Adapting to technical progress’ (MHSW Schedule 1 e). This is already possible for some tasks but doesn’t avoid the need to consider the hazards from the cleaning robots. This demonstrates the blurring between the triangle layers - when you eliminate one hazard, you often substitute it with another. Similarly, replacing cleaning using chemicals with cleaning machines that use very hot steam replaces the chemical risk with that of heat and electricity.

Reducing the risk at source, by replacing more hazardous substances with less hazardous ones is an essential step whether the cleaners are human or robots, since building users, your new robot technicians and the environment could all be affected by the substances used. Many cleaning companies no longer use chlorine-based bleaches or substances based on ammonia or solvents for this reason.

Engineering controls for cleaners can relate to storage of substances – for example, locked storage to prevent use by untrained staff, with ventilation for volatile substances to prevent vapour build-up. It can relate to how the substances are used. Mop systems with built-in dosing prevent splash back when cleaners pour cleaning chemicals into buckets of water. Long-reach tools prevent people having to hold damp cloths in their hands, impregnated with cleaning products. Replacing sprays with foams reduces the risk of inhaling fine droplets.

The substitutions and engineering controls aren’t effective without the administrative controls. I’ve seen a cupboard full of cleaning products, where some are much more hazardous than others. The more hazardous substances require the use of a face shield, as well as the usual gloves, and are only intended for use when the safer alternatives are ineffective. When asked, the staff had no idea which was which and would select the first one that came to hand, not realising the need for additional PPE.

Dealing with spills and first aid, and processes for health surveillance are all examples of administrative controls, but would you place these above PPE in your control strategy? They are important elements of limiting harm or damage once it occurs, but they are not as effective at preventing harm as the right gloves, eye protection or, where needed, respiratory protection. Some administrative controls could support the reduction layer near the top of the triangle – instructions to wipe boots on entry, handling instructions to prevent spills and prohibitions on eating in work areas could all reduce the need for cleaning.

Figure 3: COSHH control for cleaners

Conclusions

These two examples show how, in calling this a ‘hierarchy’ of control we should not fall into the trap of thinking that applying one measure near the top means we don’t need to consider any further down. Measures lower down can often be implemented more quickly, providing immediate protection for people until measures higher up can be arranged. Even then, administrative measures might remain essential to support controls further up the triangle.

The hierarchy of controls should not be seen as a wine list, where you chose one bottle of the best quality wine you can afford. Instead, they are a buffet, where you select multiple items to give you the nutrition you need.

Definitions for terms in this article:

Hazard – the thing or activity which presents a risk of harm, e.g. a frayed carpet, the act of climbing a ladder

Hazardous event – when the risk of harm is realised, e.g. someone trips on the frayed carpet, or someone falls from the ladder

Risk – the likelihood of the hazardous event occurring, and the severity of the harm which might occur.

Controls – the set of all those things that you do to reduce the risk of harm by reducing the likelihood of the hazardous event, or by reducing the severity of any harm that might result if the hazardous event happens, or both.

RoSPA offers a range of NEBOSH training courses focused on health, safety and risk management. These qualifications equip professionals with the knowledge and skills to identify hazards, conduct effective risk assessments and foster a safer, healthier working environment. Find out more at: www.rospa.com/shop/health-and-safety-courses/nebosh-courses